From Statehouse

to Bull Pen

Idaho Populism and The Coeur d'Alene Troubles

of the 1890's

by William J. Gaboury

Source: William J. Gaboury,

"From Statehouse to Bull Pen: Idaho Populism and the Coeur d'Alene Troubles

of the l890's," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, LVIII (January. 1967), 1422.

The

decade of the 1890's was the scene of economic strife, industrial warfare and

agrarian discontent which gave birth to the Populist Party. The agrarian thrust

of the party embraced the principle of free silver propounded by the mining

interests of the West. Idaho embraced Populism. Her first electoral ballot was

cast for the Populist candidate, James B. Weaver. In fact, Idaho citizens, along

with those of Colorado and Nevada, cast more than half their votes for Weaver.

The

decade of the 1890's was the scene of economic strife, industrial warfare and

agrarian discontent which gave birth to the Populist Party. The agrarian thrust

of the party embraced the principle of free silver propounded by the mining

interests of the West. Idaho embraced Populism. Her first electoral ballot was

cast for the Populist candidate, James B. Weaver. In fact, Idaho citizens, along

with those of Colorado and Nevada, cast more than half their votes for Weaver.

William J. Gaboury traces the role of populism in Idaho and its defense of the

attempts to organize the mines in northern Idaho. The efforts of the mine owners

to quell union organization and the union's reaction are placed in perspective.

The decline of Idaho populism is linked to the violence and tragedy in the Coeur

d'Alenes and the thrust of the Republican administration to destroy it as an

effective force in Shoshone County.

The decade of the 1890's

was a turbulent one in our nation's history, but for Idaho residents it was

especially stormy. Idaho was admitted to the Union in 1890 as an underdeveloped

frontier state, and it was still struggling to establish itself politically

and economically when it was hit by the nationwide depression in 1893. Prices

for farm produce sank to rock bottom. Banks, saloons, stores, and mining companies

closed their doors. From one end of the state to the other, unemployed and penniless

men walked the streets. Economic conditions were so disastrous that, as the

Coeur d' Alene Press reported, a highwayman who had operated near Rathdrum for

some time was compelled to abandon his activities because he could no longer

make a living.

Coxey's Army was another

disruptive force during this period. Deeply affected by the depression in 1894

and disappointed because the government seemed to be making no effort to help,

hundreds of unemployed laborers followed Jacob S. Coxey on a march to the nation's

capital to present a living "petition in boots." The Coxeyites called

for national road construction and municipal improvements to be financed by

government issuance of legal-tender notes. Most of the Coxeyites in the Pacific

Northwest came from the coastal urban areas - Portland, Seattle, and Tacoma.

As they headed eastward by rail, they had to cross Idaho, where many were left

stranded and destitute when the railroads refused to haul them any farther and

had them arrested if they seized locomotives on their own.

The disputes between the

miners' unions and the mineowners in the Coeur d'Alenes constituted the most

serious problem confronting Idahoans in the 1890's. Trouble first began in the

spring of 1887, when the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mining and Concentrating Company

reduced the prevailing wage scale of miners from $3.50 to $3.00 for a ten-hour

day and of carmen and shovelers from $3.50 to $2.50 per day. When the employees

went on strike rather than accept this lower wage scale, the company restored

miners' wages to $3.50, but the wages of carmen and shovelers were held at $3.00.

To protect themselves against future wage reductions, the miners organized the

Wardner Miners' Union in November, 1887 the first union in the district.

Along with wage and hour

grievances, the laborers also complained that unmarried men were forced to live

in company bunkhouses and eat at company boarding houses, that the monopolistic

company stores charged exorbitant prices, and that diseases and injuries which

the companies could have prevented were improperly treated by the company's

doctors (each employee was charged a fee of one dollar a month for medical care).

In their efforts to eliminate these grievances, the miners organized additional

unions in 1890 at Gem, Burke, and Mullan. Early the next year these three locals

joined with the Wardner Miners' Union to form a central organization officially

titled the Central Executive Committee of the Miners' Union of the Coeur d'Alene,

and commonly referred to as the Central Executive Miners' Union or the Coeur

d'Alene Miners' Union. This coordinating body, which consisted of two delegates

from each of the four local unions, remained a powerful group even after the

locals affiliated with the Western Federation of Miners in l893.

Trouble erupted again during

the winter of 1890-91, when the mineowners introduced compressed air drills.

This technological improvement reduced many skilled miners to shovelers and

carmen, resulting in a wage cut of 50 cents per day. To help maintain their

former economic status, union members asked each company to adopt a uniform

scale of $3.50 a day for all underground laborers - the rate which was in effect

prior to 1887. Most of the mining companies accepted the request with little

resistance, but it took a bitter strike before the Bunker Hill and Sullivan

finally agreed to meet the union demands.

For six months after this

wage agreement was reached, labor-management relations in Shoshone County were

peaceful. Then, in January, 1892, the recently organized Mine Owners' Association

announced that it would be forced to close most of the mines because of an increase

in railroad freight rates on ore shipped from the district. By mid-March, however,

the railroads had capitulated and restored the former rates. The mineowners

then announced that they would reopen the mines; miners' wages. they reported,

would be maintained at $3.50 a day, but carmen and shovelers would be paid only

$3.00. The Coeur d'Alene Miners' Union refused to accept the wage reduction.

In retaliation the mineowners

imported non-union men and hired armed guards and Pinkerton detectives to protect

the "scabs," even though it was a violation of the constitution and

laws of Idaho to bring an armed force into the state. Union miners attempted

to convince the armed scabs, both by persuasion and by threat, to join the union

cause or leave the area. Open fighting between pro-union and anti-union men

broke out on July 11, 1892, near Gem. During the conflict, the "old"

Frisco mill was dynamited, and several men were killed before the nonunion men

surrendered. They were given twenty-four hours to get out of the area.

When the mineowners realized

that they were losing to the unions, they sent numerous wires to Republican

Governor Norman Willey for assistance. He promptly proclaimed marital law in

Shoshone County, called out the Idaho National Guard, and requested President

Harrison to send federal troops. In addition, the Governor dispatched Inspector

General James Curtis to the Coeur d'Alenes with instructions to protect life

and property and to insure the right of every man to labor for any employer

without interference.

Curtis was even more sympathetic

toward the mineowners than Governor Willey had been. One of his first official

acts was to remove the county sheriff and appoint in his place a company doctor

whom the miners disliked. Furthermore, Curtis continually encouraged the governor

to retain martial law. The nonunion men who had been driven from the county

during the fighting were returned to the district under armed guard, and they

worked under military protection at wages of $3.50 a day for miners and $3.00

for carmen and shovelers.

Union officers, members,

and their sympathizers - nearly six hundred in all - were arrested, with as

many as 350 individuals at one time locked in warehouses and storehouses, which

were dubbed "bull pens." Thirteen were sentenced to the Ada County

jail in Boise, and four were sent to the Detroit House of Correction. By the

end of March, 1893, however, all the prisoners were free. They had served their

terms, had been pardoned, or their convictions had been reversed by the United

States Supreme Court. The former prisoners returned to the Coeur d'Alenes, where

they were welcomed as heroes.

Into this confusing and

explosive situation came a new element - the People's (or Populist) party. This

new political organization was born in Cincinnati in May, 1891. Composed mainly

of discontented farmers and laborers, the party sought reforms to help the underprivileged

and the oppressed. The first national nominating convention of the Populist

party met in Omaha in July, 1892. The platform which the delegates adopted cited

their grievances and called for action on the following crucial issues: flexible

federal currency; free and unlimited coinage of silver; a graduated income tax;

government ownership of railroad, telephone, and telegraph facilities; an eight-hour

day; condemnation of the Pinkerton system; a secret ballot; the initiative and

referendum; and direct election of senators.

The party had been organized

in Idaho late in the spring of 1892. The leaders reaffirmed the Omaha proposals

and explicitly condemned the actions of state and national authorities in the

Coeur d' Alene mining dispute. The Idaho platform extended the party's "hearty

sympathy" to the Miners' Union in its struggle against the mineowners.

Thus, for the first time, a national political party specifically aligned itself

with the Coeur d' Alene union miners in their struggle to raise their economic

and political status.

During the 1892 campaign

in Idaho, however, the Populist Party made little effort to organize or convert

the Coeur d'Alene miners. Party leaders believed that the strike and martial

law restrictions had already caused too much dissension in Shoshone County.

But in the election of 1894, Shoshone became the banner Populist County. The

Populists captured nearly every office, and in many contests their votes equaled

those of the Democrats and Republicans combined.

Although the Populists

were never successful in gaining control of the state or national government,

in Idaho they elected a United States Senator (Henry Heitfeld) and two Representatives

(James Gunn and Thomas L. Glenn), and they sent sixty-eight of their candidates

to the state legislature. In the legislative chambers at Boise, Populists battled

for pro-labor legislation. They demanded an eight-hour day for miners, an arbitration

board to settle industrial disputes, and an investigation of the 1892 mining

war. They objected to appropriations for the state militia, charging that it

was simply a tool used by the state and the mineowners to suppress labor. They

called for legislation to forbid employment of aliens, to outlaw yellow-dog

contracts, to prohibit company stores, and to abolish blacklisting. One of the

most dramatic speeches in the legislature during this period was the one against

blacklisting delivered by Edward Boyce, Populist state senator from Shoshone

County and one of the union leaders who had been sentenced to the Ada County

jail in 1892.

Senate bill fifty six

provides for no class, no special legislation, but under its provisions those

relentless persecutors, known as corporations, are prevented when they discharge

an employee from following him with a blacklist and depriving him of the means

of earning an honest living in another part of the state….Why do you

not produce some argument against it to show that it should not become a law?

No, it is not necessary: you of the republican party have the votes to kill

the bill and that is all you desire. But remember these words: the laboring

men of Idaho have asked you or bread and you give them a stone: we ask you

for justice and you treat us with scorn, but the day is fast approaching when

your action will be condemned by every man who has one drop of manly blood

in his veins.

The great Pullman strike

of '94, under the leadership of that grand general, the Hon. Eugene V. Debs,

is a striking illustration of the infamous blacklisting practiced by those soulless

corporations. When an employee was discharged by any of the railroad companies

he was given a certificate of recommendation, couched in the finest terms known

to the English language, but upon holding this paper between you and the light,

the picture of a crane turned head downwards confronts your view, which signifies

the rejection of the bearer.

Now gentlemen, I ask

you is this justice, is it right that the laboring men should be pursued in

this manner as the sleuthhound pursues his victim to death?

I am sorry to say that

in Idaho, particularly in my county, this infamous practice prevails to an

alarming extent, and you say there is no cause for this law, the laboring

men are all right…...

Despite the efforts of

Populist legislators to improve the working conditions and economic status of

Idaho laborers, little was achieved. Nearly all-Populist proposals were defeated

by Democratic and Republican majorities. Nor was there a settlement of the long-standing

dispute between the Bunker Hill and Sullivan and the Coeur d'Alene Miners' Union.

The Shoshone County labor troubles continued to plague Idaho politics, and the

Populists became increasingly involved.

Meanwhile, the Coeur d'Alene

Miners' Union was growing stronger. Depression did not seem to inhibit its activities;

membership increased, union functions were well attended, boycott and strike

orders were respected. With this new strength came uncompromising demands for

recognition, a union shop, and a wage scale of $3.50 per day for all underground

laborers.

The Bunker Hill and Sullivan,

however, remained intransigent and rebuffed all appeals for negotiation. Anticipating

trouble, the company managers organized their nonunion employees into militia

companies; the Republican State administration supplied arms and ammunition

and promised the imposition of martial law to protect property should violence

erupt. While company officials, notably those of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan,

imported nonunion men and fired all the union agitators they discovered on their

payrolls, union militants demanded the dismissal of nonunion laborers. Scabs

and management sympathizers who refused to comply with requests to leave the

district risked personal injury or death.

In November 1894, union

employees of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan struck for $3.50 per day and union

recognition. They also demanded that future differences be settled by arbitration.

Rather than concede to the union, the company closed the mine for the winter.

When the mine was reopened in June, wages were reduced to $3.00 for miners and

$2.50 for mine laborers, but the company promised to raise wages to the old

rates of $3.50 and $3.00 as soon as lead and silver prices reached a stipulated

level. The Bunker Hill and Sullivan continued to import nonunion laborers and

to employ undercover agents to ferret out union men. The union continued to

retaliate by driving company "stooges" from the county.

More and more, the county

was being divided into two antagonistic camps. Allied with the mining corporations

were the state Republican administration, "law-and-order leagues,"

and local councils of the American Protective Association, a national, anti-Catholic

organization that opposed organized labor in the Coeur d'Alenes apparently because

many union members were Catholic immigrants. On the other side, Miners' Union

officials and Populist Party leaders were now the same men fighting for the

same cause.

Conditions remained virtually

unchanged for nearly five years. The Populist Party, although no longer politically

significant on a statewide basis, was still dominant in Shoshone County. And

the struggle between the Miners' Union and the Bunker Hill and Sullivan remained

the major dispute in the Coeur d'Alenes. The company had been violating state

law by refusing to hire known union men ever since 1893, when the legislature

outlawed yellow-dog contracts; and since mid-1895 it had paid skilled miners

only $3.00 and unskilled laborers $2.50 per day.

All other mining companies

in the district were unionized, and all companies except the Last Chance at

Wardner, which was dependent upon the Bunker Hill for electric power, paid the

union scale of $3.50 for all underground employees. Bunker Hill and Sullivan

managers justified their lower wage scale by noting that the Wardner mines were

dry operations, whereas the Canyon Creek mines were wet operations, which meant

that employees had the additional expense of purchasing costly rubber clothing.

Union members, on the other hand, believed that the Bunker Hill and Sullivan

were a threat to the wage scale and to union shops in the district. They protested

that the Bunker Hill and Sullivan maintained its privileged position by organizing

militia companies of scab" employees who were supplied with arms by the

state during the administration of Governor William McConnell.

By mid-April, 1899, the

union had secretly organized a number of Bunker Hill and Sullivan employees,

and it hoped soon to have enough strength to paralyze the company with a strike,

and thereby force union recognition and union wages. Edward Boyce, formerly

a Populist state senator and by this time president of the Western Federation

of Miners, was on hand for consultation and advice. On the morning of April

18, notices were posted on Bunker Hill and Sullivan properties, inviting all

men who were not members of the Wardner Union to join immediately.

On April 23 Bunker Hill

and Sullivan fired seventeen employees whose union affiliation had been discovered

the night before. That evening the company raised wages 50 cents per day (but

still not to the union level of $3.50 for all employees) and began to dismiss

more of the union members. The union threatened nonunion Bunker Hill and Sullivan

employees and warned them to join the Wardner Miners' Union or leave town. Democratic

Governor Frank Steunenberg and Populist county officials, Sheriff James Young

and Assessor Michael Dowd, urged union and management to arbitrate and negotiate.

Bunker Hill's Assistant Manager Frederick Burbidge refused. He insisted that

the union men were not his employees and that he would not meet with any union

committee. Within five days, however, three hundred of the Bunker Hill's crew

of four hundred were back at work on company terms, and the strike appeared

to be over. The Miners' Union apparently had suffered another defeat at the

hands of the crafty Bunker Hill and Sullivan managers.

But the struggle was far

from over; actually, it had only begun. Assistant Manager Burbidge received

the first intimation of more serious trouble in a telegram of April 29th warning

him that the Canyon Creek mines were closed and that the miners were coming

to Wardner to assist the local union. At first, Burbidge believed that it would

be a "moral suasion" demonstration, but when he learned by a later

message that the men were masked and armed, he appealed to Governor Steunenberg

for assistance. Burbidge advised his employees to abandon the plant and "look

out for themselves". He himself fled down the railroad track toward Spokane.

Burbridge had reason to

fear. At approximately ten o'clock that morning 150 to 250 rugged miners boarded

a Northern Pacific train at Burke, the mining camp farthest up Canyon Creek.

They forced the engineer to carry them to the Bunker Hill and Sullivan site

at Wardner, stopping en route to pick up 3,000 pounds of dynamite and several

hundred more miners, many of them masked and armed.

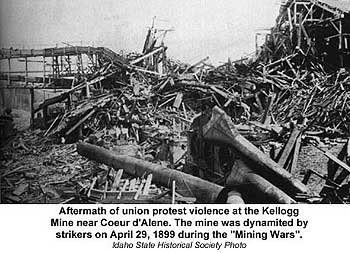

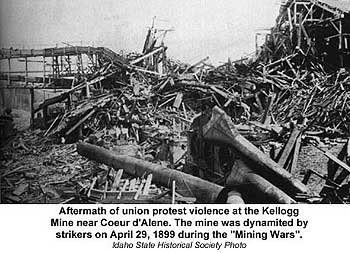

At Wardner the rebellious

miners dynamited and destroyed the Bunker Hill and Sullivan concentrator and

burned the office and the boardinghouse. A group of miners captured and harassed

three Bunker Hill and Sullivan employees, fatally wounding one of them with

rifle fire, and somehow managed to kill one of their own members. When the destruction

was completed, the miners returned to the depot, clambered aboard the train,

and fired their guns in a five-minute victory fusillade as the "dynamite

express" headed slowly back up the canyon.

The miners were back at

work the next day, and Shoshone County was quiet, as if nothing unusual had

happened. The tranquillity was short-lived, however, for federal troops were

already on the way to the Coeur d'Alenes, and any male who remained in the district

became subject to arrest and incarceration in boxcars or in the notorious "bull

pen." The trials and legal investigations which followed were conducted

primarily for the purpose of proving the guilt of the unions in the Bunker Hill

dynamiting.

The Populist Party became

deeply involved in this dynamiting episode, and it was the only political organization

in the state to sympathize with and support the union cause. United States Senator

Henry Heitfeld, accompanied by Senator Thomas H. Carter (Republican, Montana),

Edward Boyce, and William R. Goldensmith (former Populist State representative)

called on President McKinley and protested the military actions of the national

government in Shoshone County. Populist attorneys helped to defend hull-pen

inmates, and Populist newspaper editors, while deprecating the use of violence,

placed the initial responsibility for the trouble on the Bunker Hill and Sullivan.

The shortsighted and unjust policies of the company, the Populists argued, forced

the miners to take violent action.

Not only were the Populists

sympathetic toward the unions, but a number of party leaders were directly implicated

in the April 29 uprising and its immediate after-math. Among those charged with

planning the riot was Edward Boyce, president of the Western Federation of Miners.

Boyce had been in Wardner conferring with local union officers only a week before

the explosion. According to May Arkwright Hutton, the miners discussed the possibility

of "getting up a demonstration meeting and marching to Wardner in a body."

Boyce thought that "it might be a good plan, but he believed that the companies

would grant their demands in a few days." In 1906 Harry Orchard confessed:

"I know that Edward Boyce planned and approved the blowing up of that mill.

I have been told so by a man that knew all about it. "23 The editor of

the Wardner News reported,

If Edward Boyce is arrested

and the judicial X-ray turned upon him there will be found within the black

matter of his wicked brain the complete plans and specifications of the atrocious

crimes committed here last Saturday.

The most sensational official

charge against Boyce was made by Governor Steunenberg before the House Committee

on Military Affairs:

I learned that Ed Boyce…was

in the country 10 days before the explosion of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan

mill, and at that time he inaugurated or perfected this conspiracy by, choosing

20 men from different organizations in that county and swearing them. These

20 men chose one each and swore him, and the 40 each chose a man and swore

him, and the 80 each chose a man and swore him. In that way there were at

least 160 men in this conspiracy to do this thing, sworn to secrecy.

Boyce denied these conspiracy

charges.

During June 1899, Michael

Dowd, the Populist county assessor, became involved in a spirited controversy

which grew out of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan explosion. For years the Bunker

Hill and Sullivan Mining Company and the Populist assessors had disagreed on

the value to be placed on company property for assessment purposes. State law

required assessments at actual cash value. But the two sides could never agree

on the value of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan property. In 1898 the company estimated

its holdings at $119.000, while Populist Assessor J. J. Purcell evaluated Bunker

Hill's property at $200.000. The company ignored the assessor's evaluation and

paid taxes on only $119,000. In 1899 Assessor Dowd declared that the Bunker

Hill and Sullivan was worth $248,000, but the company managers set the figure

at $123,000. Following the explosion, the company claimed that $250,000 worth

of property had been destroyed. Upon hearing this declaration from the company,

Assessor Dowd prepared to sell the Bunker Hill and Sullivan properties for delinquent

taxes. Judge J. R. McBride of Spokane, who represented the company, hurriedly

secured an injunction restraining the Populist official from any such act. He

argued in his petition that the county officers had discriminated against the

Bunker Hill and Sullivan because of the company's refusal to employ only union

men.

A large number of Populists

were arrested by state and military authorities. Three prominent party leaders

in the county who spent time in the Wardner bull pen were William Stewart, editor

of the Mullan Mirror, who had incurred the wrath of Idaho officials by his attacks

upon their policies, and William R. Goldensmith and Ed Flanagan, both of whom

had represented Shoshone County in the 1897 legislature. Flanagan, who at the

time of his arrest was a justice of the peace in Mullan, told the House Committee

on Military Affairs that he was arrested without charges and confined in the

bullpen for eighty-three days. William Powers, constable at Mullan and president

of the Mullan Miners' Union, was arrested while on his way to Wallace to testify

before the United States Industrial Commission. Deputy Sheriff Thomas Heney

was imprisoned from June 23 to October 3. During his imprisonment the military

authorities tried to force him to dig a ditch around the bullpen. Heney refused,

claiming that he was sick. The state authorities, he testified, ordered his

release on September 22, but the military officers refused to free him until

he worked on the ditch.

I was never accused of

any crime (he reported) nor was I indicted by any grand jury: neither was

I informed of any charge against me. I asked to be allowed to give bail to

any amount up to $100,000, which I could easily have furnished, but this,

too, was denied. We refused to work because we were American Citizens, convicted

of no crime and did not believe they had the right to make slaves of us.

The most punitive and offensive

actions against Shoshone County Populists were the arrest, imprisonment, and

impeachment of Sheriff Young and two county commissioners. William Stimson and

William Boyle. On May 6 State authorities demanded that the three Populists

officials resign. When they refused to do so, they were arrested and confined

in a small guardhouse near the main Wardner prison. Young described the conditions

to the Industrial Commission:

I was put in one corner

and told not to converse with anyone: if I did it would go hard with me. I

was told this by the officers. I think I was there about 4 hours when one

of the County commissioners was arrested and brought in. Mr. Boyle. He was

placed in another corner and told the same thing. Presently in came Mr. Stimpson

and he was placed in another corner...We were not allowed to say a word to

each other. We just simply laid down in the straw on the wet ground. It was

raining nearly every night and day, and for 3 weeks we were kept in that condition,

with the exception of after the first five days we were allowed to converse

with each other a little....Our bedding was constantly wet and the ground

was constantly wet. Mr. Boyle is about 60 years old and contracted a severe

cold and has remained deaf from the effects of it ever since, and can hardly

hear anyone speak at the present time.

In the impeachment charges

against the Sheriff, Idaho Attorney-General Samuel H. Hays complained that Young

knew of the riot plans long before their occurrence, but that he made no attempt

to prevent the destruction or to arrest the rioters afterwards. In fact, said

the Attorney General, Young had "connived at and assisted in" the

destruction of the Bunker Hill works. Sheriff Young denied the charges. He claimed

that the first knowledge he had of the disturbances was at 10:30 a.m. on April

29th, when a deputy sheriff came into his office and notified him that there

was a trainload of armed and masked men at the Wallace depot evidently bound

for Wardner.

That was the first knowledge

I had of it. I ran down to the depot, and took in the situation. The train

was starting up and the thought struck me that if there was any possible show

to do anything with the armed mob it would be to get on the train and go down

with them; it was the only show to do anything, as the train was starting

out. I did that; I got on the end car, and when I got in the car I was told

not to get out of the car or to try to get out of it. I was very much surprised

to find them all masked and armed. Well, of course, I didn't attempt to get

out of the car at, any time going down.

At Wardner Junction, Young

ordered the men to disperse, but to no avail. When he asked for assistance,

he said, the men simply laughed and refused to help. Testimony at his trial,

however, indicated that if Young was not in complicity with the rioters, he

was at least on speaking terms with them. Herman Cook, the last witness, testified

that, after the explosion, he heard the Sheriff ask a masked man, "Who

was killed?" "Smith," was the answer. "Schmitty from Burke'?"

asked the Sheriff. According to Cook. Young then inquired whether the men had

provided for the safety of women and children in the vicinity before destroying

the mill.

Probably the most damaging

evidence against Young came from his own testimony. At the moment of the explosion.

The Sheriff declared, he was having lunch at Mrs. McLeod's. He told Special

Prosecutor William E. Borah,

I followed the masked

men part way down to the mill, but there I was stopped. Later they let me

go, and I went over to a friend's house and got some lunch. I was in the house

drinking some milk when the explosion went off.

Concerning the dynamiters,

Young said that he believed the Canvon Creek miners were the guilty ones. But

that he and H. F. Samuels, the Populist county attorney had agreed it would

be best to wait until "the miners had settled down before making any attempt

to capture them." "Settle down where'?" demanded Borah. "Settle

down here, or over in British Columbia?"

On July 10 1899, Judge

Cicorge H. Stewart rendered judgment in favor of the prosecution, sustaining

every allegation against Sheriff Young. In a strong statement castigating the

Sheriff, Judge Stewart declared: "The highest peace officer of the county,

conducting himself as he states in his own evidence, has disgraced the office

to which he has been elected, and has shown himself to be incompetent and unfit

as a public servant."

Although the chairman of

the board of county commissioners, Moses S. Simmons, had not been arrested,

he was charged along with Commissioners Boyle and Stimpson with dereliction

of official duties. The state insisted that the commissioners had been warned

of impending trouble by Assistant Manager Burbidge as early as April 26. Yet,

state officials said, no meeting of the board had been called, and the commissioners

had failed to secure responsible peacekeeping operations from the Sheriff. The

three commissioners denied that they had any advance notice of a contemplated

riot. The Populist defendants claimed that, when they had consulted with Sheriff

Young prior to April 29, the Wardner situation seemed under control. Nonetheless,

Judge Stewart declared that the three commissioners had disregarded and neglected

their official duties and had demonstrated their incompetence and unfitness

for the public trust imposed upon them. Boyle, Stimson, and Simmons were removed

from office, and Governor Steunenberg appointed in their places two Democrats

and one Silver Republican. The new commissioners in turn selected a Republican

as county sheriff.

Four Populist officials

were removed from public office, and hundreds of party members were in the bullpen.

James Young estimated that 80 per cent of the prisoners were Populists and a

Populist doctor, F. P. Matchette, said he would pay five dollars a head for

every prisoner who was not a Populist. With these facts before them Populist

Party sympathizers charged that the policy of the state and military authorities

was to destroy the party in Shoshone County. The Populist Idaho State Tribune

stated:

Behind this pretended

prosecution of parties who destroyed the Bunker Hill mill is a political conspiracy

to subvert the government of Shoshone County. The real scheme is to displace

the officers who were elected on the people's party ticket and fill the offices

with men not the choice of the voters of the county.

Even the Kootenai County

Republican insisted that "the whole proceeding appears to be nothing more

nor less than political persecution." Bartlett Sinclair, the governor's

representative in Shoshone County, however, denied that politics was involved

in the state's activities in the district.

Intentional or not, in

prosecuting and suppressing the Coeur d'Alene Miners' Union, the state destroyed

the last major remnant of the Populist Party in Idaho. Under the infamous "permit

system," no one could work in the Coeur d'Alenes unless he stated that

he had not participated (actively or otherwise") in the Bunker Hill and

Sullivan incident and agreed to abjure forever allegiance to the Miners' Union.

More over, regardless of any papers he might sign, no applicant was issued a

work permit if state authorities believed that he had participated in the events

of April 29. The permit system and martial law continued well into 1900, and

many loyal union members and Populists fled the state. Idaho officials and Bunker

Hill and Sullivan authorities cooperated to form a new 'industrial union"

in the county which bore little resemblance to the Miners' Union that Shoshone

County residents had previously known. The bylaws and ritual of the new organization

were written by James H. Hawley, one of the special prosecutors.

The official position of

the state - and the common belief of many people - placed the entire responsibility

for the destruction of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan property upon the leaders

of the Coeur d'Alene Miners' Union. That a demonstration against the Bunker

Hill and Sullivan was planned and organized by union leaders seems undeniable.

But there is considerable evidence that the violence was the result of actions

by individual hotheads or radicals within the unions, and that it was not necessarily

sanctioned by the unions or by the principal union leaders.

In general, it seems, both

labor and management must share the blame for the loss of life and property

in 1899. Union leaders evidently authorized the mission to Wardner and tolerated,

if they did not plan, the violence by the rank and file. The Bunker Hill and

Sullivan management, concerned primarily with its own profits, had for years

refused to heed the reasonable requests of the laboring man. Throughout the

decade Bunker Hill and Sullivan managers had violated Idaho statutes and reaped

profits with little concern for the welfare of others or for changing socioeconomic

conditions.

Although the Populist Party

had been closely associated with the unions throughout the decade, there is

no evidence that the organization encouraged or was responsible for the destruction

of property or the shootings in the Coeur d'Alenes. The individual Populist

was likely to be so concerned with improving the conditions of union labor that

he would at times forget that the rights of the opposition - even corporation

employers - must be respected. But the party as a whole was devoted to peaceful

labor-reform legislation and deplored the fact that industrial relations had

deteriorated to a level where violence appeared to be the only recourse.

National conditions were destined

to make the 1890's a decade of political and economic turmoil in the West, but

more generous and sympathetic policies on the part of state and corporate officials,

coupled with union restraint, could have saved Idaho from the chaos in the Coeur

d'Alenes.

A critical contemporary account

of the mining troubles and their aftermath is May Arkwright Hutton, The Coeur

d'Alenes,

A Tale of the Modern Inquisition in Idaho (Wallace, Idaho: n.p., 1900).

Of interest is Benjamin H. Kizer, "May Arkwright Hutton," Pacific Northwest

Quarterly, LVII (April, 1966), 49-56.

An excellent over-all discussion is in Beal and Wells, History of Idaho, II, chapter

4, "Populism and Free Silver, 1890-1896," and chapter 7, "Martial

Law in the Coeur d'Alenes."

Those interested in Populism should consult the classic in the field - John D.

Hicks, The Populist Revolt (Minneapolis, 1931).

A critical examination is Richard Hofstadter, "The Folklore of Populism"

in The Age of Reform from Bryan to F.D.R. (New York, 1955).

Favorable studies include Norman Pollack, The Populist Response to Industrial

America: Midwest Populist Thought (Cambridge, Mass., 1962), and Walter T K. Nugent,

The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism (Chicago, 1963).

This article was excepted from "The Idaho Heritage", Richard W. Etulain

and Bert W. Marley, editors, with permission from Idaho State University Press.

The

decade of the 1890's was the scene of economic strife, industrial warfare and

agrarian discontent which gave birth to the Populist Party. The agrarian thrust

of the party embraced the principle of free silver propounded by the mining

interests of the West. Idaho embraced Populism. Her first electoral ballot was

cast for the Populist candidate, James B. Weaver. In fact, Idaho citizens, along

with those of Colorado and Nevada, cast more than half their votes for Weaver.

The

decade of the 1890's was the scene of economic strife, industrial warfare and

agrarian discontent which gave birth to the Populist Party. The agrarian thrust

of the party embraced the principle of free silver propounded by the mining

interests of the West. Idaho embraced Populism. Her first electoral ballot was

cast for the Populist candidate, James B. Weaver. In fact, Idaho citizens, along

with those of Colorado and Nevada, cast more than half their votes for Weaver.