| A tool is anything which has been modified to make work or survival easier. Everything which has been modified or manipulated by a human or animal becomes a tool. |

Humankind has successfully survived because within our cultures we use many different types of tools. Tools are used all of the time by peoples living everywhere on Earth. Some types of tools are quite ordinary, but many are amazingly unexpected. Humans are not the only creatures which use tools. Birds build nests, and nests are tools. Chimpanzees chew leaves and then use the partly chewed leaves to soak up water to drink; the leaves are tools. Gorillas "fish" for ants using a twig; the twig is a tool. So, what is a tool, anyway?

|

| Stone vessel (bassalt pot). Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Tools can be incredibly simple; such as a rock used to crush seeds. Some tools are incredibly complex; consider the computer used to write these words into sentences. There are some tools that are not immediately obvious as being tools; like clothing, blankets, shelters and houses and fire.

Often tools must be used to skin the hide from a deer, which is sewn together using an awl and sinew thread to make clothing. Consider the saw which cuts the wood, which is hammered into place as a house is built. The knife, awl, sinew thread, hammer and saw are all tools used to fabricate other tools like clothing and shelter. All of these tools have been modified and manipulated to make work and survival easier.

The earliest tools were crudely chipped stones used by early humans, living in Africa, about 2 million years ago. Those crude stones, modified into tools, were used to make work and survival easier. Eventually, because tools had become more complex, the skill of tool making became necessary and, through experimentation, stone tools were further modified and made more efficient and intricate.

As the knowledge and science of toolmaking expanded the toolmakers began to invent tools designed to suit a particular job or need. This succession of tool use, tool modification, tool making and tool invention and deign to suit a job required much time (2 million years), experimentation and invention to occur. In the end humans were using tools in every aspect of life and survival.

|

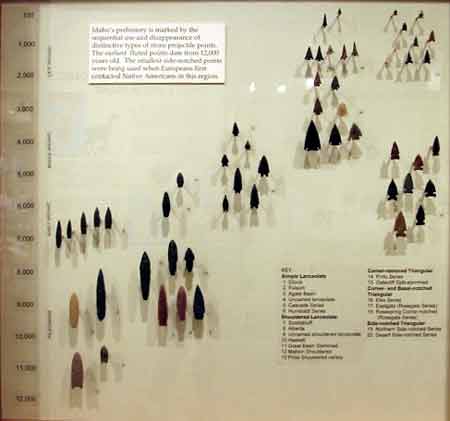

| Projectile point sequence for Eastern Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

The "People" had seven technological systems based on the different material available as resources: stone, wood, plant and fiber, basketry, pottery, bone-horn-antler and hide.

Stone working made tools for processing seeds and other plant parts, for cutting wood, shredding plant fibers, incising and polishing bone-horn-antler and cutting and scraping hides. Various types of stone had properties which allowed them to be flaked, pecked or ground.

For stone to be fashioned into a useful tool it must be hard, tough and of a smooth, fine-grained consistency. Flint, chert, jasper, chalcedony, agate and obsidian are all types of stone which are solid, but have the property of a cooled, heavy liquid which is also somewhat elastic and free of flaws and cracks. These particular types of stone were the most frequently used for tools because they have a fine-grained consistency and behave like glass, and will break along a controlled line, rather than crumbling as will granite. Breaking along a controlled line meant that a toolmaker could break off flakes that were razor-sharp.

By working these assorted kinds of stone with various techniques many different tools were fashioned. The finer-grained the stone, the flatter and more leaf-like the flakes that could be chipped loose from it.

The size and shape of stone flakes could be further controlled by the ways in which they were broken from the original stone. The flakes could be knocked loose by a hammer stone (percussion flaking) or pried loose by a pointed stick or bone (pressure flaking). With percussion flaking the angle at which the hammer stone blow was struck was changed to produce either a small, thick flake or a large, thin one. Also, different kinds of hammer stones made different kinds of flakes. Relatively soft hammers of woods or bone made on kind of flake, hard stone hammer made another. Pressure flaking, using a wooden or antler point pressed against the edge of the stone, would make a finished, sharp edge. Even the way a tool was held while it was made affected the kind of flake that was struck from it: when it was held in the hands, the results were not the same as when the stone was held on a rock anvil.

Every toolmaker had to have a good deal of skill, based on necessity, on years of practice, and on an intimate knowledge of the natures different stones. For each stone has its own qualities, which vary further depending on whether the stone is hot or cold, wet or dry.

Stone could be flaked or pecked and ground. In flaking, the toolmaker first selected a stone that had suitable characteristics. This core nodule was struck with a hammer stone. Conchoidal flakes, which are cone shaped, were made in this way that could then be used to create smaller finished tools like projectile points, scrapers and drills. A core with flakes removed to create a sharp edge could be used to chop down trees and shape wood.

In pecking and grinding stone tools, the toolmaker often first selected a core nodule that was about the shape of the tool he wanted to produce. It took a lot of time and effort to peck out a pestle or mortar for pulverizing nuts or a mano and metate for grinding seeds. The surface of the core was pounded withy a hammer stone roughly to the desired finished shape. Then, the surface might be smoothed through grinding. As the ground stone tools wore down with use, they would be resharpened using the pecking technique.

|

| Shoshoni Bow and Arrow. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Wood-working was often a difficult, time-consuming task for people without metal tools. In building a shelter, for example, pieces of wood were used that were about the right size and shape for the task, simply because stone axes and adzes were not terribly efficient. Dwellings were often constructed along streams, which supplied drift wood for structural supports, as well as tules and willows which would cover the framework. Wood for other tools like bows and arrows had to be laboriously shaped. A juniper limb might be selected because it was about the right thickness for a bow. Cut off the tree, the limb was then split into halves or quarters with a stone or antler adze, and scraped to shape with stone scrapers.

Larger projects requiring the cutting or trees usually meant that fire had to be used in some combination with the stone axes. The tree was girdled with fire, the sides of the trunk charred, and a stone axe used to chop out the charcoal. This process would be repeated until the tree could be felled.

Within each community of the "People" each gender had certain jobs which were to be performed. The various jobs required tools and some tools were used only by the gender performing a particular job.

Generally, the men hunted, provided protection for their families and communities and were the toolmakers. These occupations required many different varieties of tools, and tools to produce those tools. Tools used by the men included: duck decoys, nets, knives, hammer stones and the tools used for making tools, the spear & atlatl, the bow and arrow, anvil, hand pump drill, awl, and adze.

The occupations of the women were more extensive and included: gathering plants, sewing, food preparation and cooking, tanning hides, weaving, slaughtering animals and caring for children. The tools used by the women were: nets, baskets, knives, scrapers, digging stick, awl, sinew, cradle board, winnowing tray, mortar and pestle and the teshoa.

|

| Northern Paiute mans Sagebrush shirt. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Whether, used by men or women the tools were all made of plant fibers, stone, sinew, hide, bone-horn-antler and wood.

Many of the tools used by the "People" in Idaho were made from plant fibers. Plants like dogbane was pounded to produce fine, tough fibers that were twisted, by repeated rubbing on the thigh, into longer strands that could be used to make cordage. Through use of knots, this cordage was transformed, through weaving, into a variety of useful and beautiful objects. Cords became carrying bags, nets for ensnaring animals, arts of nooses and traps, and elements of composite tools of different materials. Cordage was also woven and tied into clothing like aprons, skirts and capes.

|

| Shoshoni baskets. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Today, we most often find stone tools in the archaeological record, either on the ground or hidden in the soil layers of an archaeological excavation. However, the "People" mostly used tools of perishable materials like fiber and basketry. Consequently, many tools are not preserved in the archaeological record.

Baskets were woven from all kinds of plants, from various kinds of grasses, willows, and tules or rushes. Twined and coiled baskets were both made, and were often gaily decorated with designs done in natural plant and mineral dyes. Baskets were common tools for storing plant and animal material that needed to be kept off the ground and away from pests. Baskets transported the family possessions when the "People" traveled. Some baskets were small and open, others were larger with rigid walls and lids. Baskets frequently hung from the rafters of the dwellings and assumed places of honor in the house as cherished heirlooms.

|

| Shoshoni cooking pot. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Pottery was made, but it was never as important as crafts in fiber and basketry. Usually, people made pottery as it was needed at campsites for cooking and storing food and other materials.

Local clays were taken from stream banks, mixed with water, and coiled and shaped into vessels. The formed pots were then left near the fire to be carefully dried. When ready, the pottery was placed on a bed of coals, and a fire built around it. Potters carefully watched their vessels for a change in color showing that the temperature had gone high enough to harden the clay. The pot was then removed and used to hold water, boil meat, or store seeds. Pottery was brittle and expensive to make, and usually stayed at the campsite until people returned to use it again.

|

| Bone Awl. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Bone, horn, antler and hide from animals supplied all kinds of useful tools. Hides were cured and shaped into clothing. Hides, horns and hooves could be boiled to make glues that held projectile points to shafts or sinew-backing to bows. Sinew was used for all manner of tasks that required something to be tied to something else. It was strong, durable, and water-resistant.

Horns were used for cups and spoons. Antlers were used to flake stone into tools, and could be used for any type of tool that had to be strong and durable.

Bones were cut and ground to shape as sharp tools like awls for hide-working and basketry and as the hook on the end of an atlatl into which the spear was notched. Bone needles were used to sew hide clothing.

Hides were stripped from bison, antelope, mountain sheep, deer, rabbits and other animals, and cured for all kinds of uses. Most often, hides were cleaned, stretched, and left in the sun to dry. When dry, the hides were scraped down to the thickness that was wanted. Hair might or might not be removed. Once the hide was clean and thin, animal brains were rubbed in to soften the hide. If the makers wanted to make it water-resistant, they would build a willow frame, stretch the hide over the frame and build a fire, using "green" wood, which would smoke the hide.

The tools and lives of the "People" were intimately related to their natural environments. Technology was limited by resources in the environment, and lack of metal tools meant that people had to work very carefully within what nature provided. Stone, fiber, basketry and hide crafts were highly developed. Wood-working and pottery less so, simply because available tools were not terribly efficient in working wood or producing lots of pottery.

|

| Ute woman using a metate and mano. Photo by L.C. Thorne, Thorne Studios, Vernal, Utah. |

Dependent upon the natural products of the environment for their needs the tribes of "People" living in Idaho had to invent tools and weapons which would serve to provide for all their necessities. Their ancestors had brought the knowledge of toolmaking with them from Asia at the end of the Pleistocene. However, over many thousands of years the toolmakers had made improvements and changes in the tools to meet the changes in the plants and the animals. The "People" formed tools from stone, wood, plant and animal fibers, horn, antler and hide. Their workshops were out-of-doors, and they took advantage of every possible resource to ensure survival of their families and cultures.

Idaho, with it's surrounding mountains and wide plains, shows a broad range of temperature, precipitation, and local climates. Part desert, part high country, this landscape is both harsh and productive. People needed tools to harvest and use the natural products of this diverse environment. Some tools, like fire, ensured basic survival. Other tools, like grinding and pounding stones, allowed seeds and pin on nuts to be made into flour suitable for hard tack. Additional tools were weapons. Tools such as the atlatl and spear brought down deer and larger game that supplied meat for eating and raw materials for more tools like thread, awls, needles and clothing. Eventually, by about 500 A.D., the atlatl and spear were improved upon and replaced by the bow and arrow.

The "People", dependent upon the natural world, wasted little. When out hunting, or moving throughout their range, the "People" gathered plants. Such plants as dogbane, also called hemp, provided fibers that were twisted into cordage. Cords were used to make nooses to capture small animals, nets to catch rabbits and strings to hold together twists of rabbit fur for winter robes. Other plants like tule and willow ere collected for making baskets that stored raw materials for future use. They also supplied the covering for dwelling roofs and mats for dwelling floors.

|

| Digging stick and Camas bulbs.Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Edible plants such as rice grass and camas were important in the diet. Growing in dense stands, these plants were easy to gather and highly nutritious. The tribes living in Idaho had a store of knowledge about what plants were useful, and would gather these species as they moved about the environment. Visits to certain areas would be timed to coincide with the ripening of grass seeds, nuts and berries. Campsites would be chosen for their closeness to water and sheltered aspect. Willows and tules were found near water sources, as were other important plants and animals that could be gathered.

People moved about the landscape not only to gather plants. Movements, from one locality to another, were also intended to sample animal resources. In general, plants and small animals supplied most of the diet. Small animals were hunted all the time. Nooses, snares, and traps, made up of fiber cordage, were set up near camps to take small animals that lived there or were attracted there because of peoples' activities. Because of their small size, rodents were seldom hunted except by little children practicing their skills with snares and weapons. Most small animals were trapped in dead-falls made by propping up a stone with a stick, then rigging the trap to fall when the bait was taken.

Fishing was an important seasonal activity, although, some fish could be caught all year round. Available throughout the year, bottom-feeding, scavenger species, like suckers and carp, were usually caught by hook-and-line. Sloughs and river channels near camps were favorite fishing spots for young and old anglers.

Seasonally migrating species, like the salmon, were not found in all of Idaho's streams, but where they did occur, they were a focus of great seasonal activity. Families and bands would come together at favorite fishing spots to catch salmon in nets, weirs, and with spears. The fish were taken, dried, and used as a stored food source throughout the year. While going to the salmon runs, people would gather camas and other plants using tools called digging sticks, as well as the small and large animal species they might find.

|

| Northern Paiute Duck Decoy. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Waterfowl, like ducks, were also gathered whenever possible. Marshes, ponds, and backwaters, where basic raw materials like tules and willows grew, also supplied migrating and resident waterfowl in quantity. The waterfowl could be caught by hand, lured with duck decoys made from the tules and willow, trapped in corded nets, or shot with bows and arrow.

Some small and large animals, because they are social species, can be herded and gathered in large numbers. Rabbits, antelope, mountain sheep, deer and bison were all important animals because they could be lured or driven to waiting hunters, where few would escape.

Families and bands would travel to selected spots to drive hundreds of rabbits into long cordage nets, made from plant fibers, which were strung out over hundreds of meters. Rabbit meat was delicious, and rabbit pelts were used for winter clothing. Antelope are naturally curious, they could be lured by hunters sitting quietly and waving some interesting object. Antelope could also be by hunters wearing antelope skins, who worked carefully around the herd. Mountain sheep, a naturally skittish animal, could still be easily taken by cooperating hunters. Some hunters, would skirt a game trail, and take up positions that were out of sight, from which they could select animals as other hunters drove them up or down the trail. Bison were taken by stalking hunters or by large drives of cooperating men, women, and children. Individual hunters would try to get the herd moving in a given direction. Once moving, the herd could be kept on course by line of waving men, women and children, or by piles of rocks and brush. Channeled in this way, a whole herd would be driven off a cliff, to fall at the base in a huge mass. Then, the families would set up camps near the kill site and the bison would be skinned for their pelts, meat, and bone marrow. Hides might be cured at the site for clothing, and meat dried for transport elsewhere and storage.

Almost every activity required close cooperation amongst family and band members. Day-to-day activities were often done independently by family members, but journeys to fishing, gathering and hunting sites were made by cooperating families and bands. Successful fishing, gathering and hunting expeditions like these required large numbers of people. Rabbit and bison drives, or pin on nut harvests, were fun, social occasions, when people came together for dances, ceremonies and gossip. It was important to gather nutritious foods and raw materials for tools, but these events also served to keep social groups of people together.

|

| Clovis point. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

Archaeologist have found enough stone and bone tools throughout Idaho to confirm the presence of the "People". One of the oldest sites in Idaho is the Simon site near Fairfield. There, W.D. Simon discovered distinctive stone tools, now called Clovis points, that were made by Idaho's Pleistocene hunters. Mr. Simon accidentally uncovered 5 large Clovis points and over two dozen other stone tools as he was repairing a roadway through his ranch. Clovis tools are made of beautiful stone that was probably collected from any miles away by the "People" who camped at the Simon site.

The first known Idaho "People", and the tools they made, take their name from the Clovis site in New Mexico, where this type of tool was first reported. Clovis points are fairly large, with the most distinctive aspect being the "flute" or "channel flake" that was removed from each side of the base of the point.

To make a Clovis point the toolmaker struck a block of stone with a heavy stone hammer and removed a large flake. The flake was then shaped using a smaller hammer made of stone or antler. The point was then thinned using an even smaller hammer and more carefully placed blows. Finally, using pointed antler or bone, small flakes were pressed off the point to achieve the distinctive shape of Clovis points.

Clovis People were very skilled hunters. Their primary prey consisted of mammoths, camels, giant bison, horses, and musk oxen. Although little is known of their actual hunting techniques, we are fairly certain that some Clovis hunters trapped their prey in bogs or shallow canyons. They may have also separated young or wounded animals from large herds and surrounded the single animals with spear- wielding hunters.

The large animals who lived during the Pleistocene are extinct because of climatic change, over-hunting, or disease. As they disappeared, the

|

| Folsom point. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

hunters turned their attention to smaller prey. As a result, Clovis points were replaced by smaller Folsom points. Folsom points are much like Clovis points except they are shorter, thinner, and more delicately made. They are among the most beautiful and well-crafted stone tools in North America. Like Clovis points, the most distinctive feature of the Folsom point is the single longitudinal flake that was removed from each side of the point. It is believed that this flake was removed in order to make the point easier to attach to a spear or spear foreshaft. It must have been very important since many Folsom points were broken while trying to remove these "flutes" or "channel flakes". Although the reason is uncertain, were only used in Idaho for a short time. They were replaced by several other styles of points which lacked the distinctive flute.

|

| Hasket Point. Courtesy of the Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello Idaho |

The point that followed the Folsom points in time are called "Plano" points. They are now generally long and narrow. One common variety of "Plano" point found in Idaho is the Haskett point names after a site near American Falls discovered by Mr. Parley Haskett, of Pocatello. Haskett points were used to hunt bison and mountain sheep.

Haskett point were probably fit onto spears withy deep sockets and drilled into the end in which the tapered stem of the Haskett point was inserted and secured with a form of glue called mastic. Mastic was made of a mixture of tree pitch and ash. The pitch was first melted near a flame, then ashes stirred into the molten material. Before cooling completely, the mixture was formed into a cigar-shaped glue stick that hardened upon cooling. To use the mastic, one only needed to re-heat a portion of the stick and it would again soften. It could then be used to glue a point to a foreshaft, a knife blade or scraper to a handle, or it could be melted to form a thin waterproof layer over sinew wrapping.

The spear points were all dulled on their edges near their bases. This dulling helped prevent the sharp edges of the points from cutting the wrapping that tied the points to the shaft. These edges were dulled by rubbing them with an abrader made of a course stone.

In addition to stone spear points, the "People" used a wide variety of special stone tools to work bone and wood, prepare leather, harvest food plants, and skin animals. One of the more common stone tools is called a "biface" by archaeologists. Bifaces served as multi-purpose tools, somewhat like our modern Swiss Army knives. They were used to saw, slice, dig, chop, and could be resharpened many times. Some bifaces were shaped into spear or dart points. Bifaces were made from a variety of stone types, including obsidian, chert, jasper, chalcedony and agate. Other varieties of stone tools were made on carefully rounding one end of a blade or flake. These were used to remove hair and fatty tissue from animal hides so leathers could be produced for shelter and clothing. Scrapers were made in all shapes and sizes.

Other biface tools were spokeshaves, burins and backed blades. Spokeshaves were made by taking a long slender stone blade, then shaping a crescent-like indentation on one edge. This indentation was then drawn down the length of a branch of a tree limb to give the spear its desired shape. Bruins were used to engrave bone and carve wood, and backed blades were used to cut meat or other soft materials.

Leather was tanned and made into clothing for the cold Idaho climate. To make clothing, pieces of leather were sewn together by first piercing holes at pre-measured intervals using a sharp bone awl. Next, the pieces were sewn together using sinew as thread, and needles made of cut and polished bone. Sinew was made by removing long pieces of tendon from the backs and low legs of large animals. After the tendon had dried, it was pounded over a smooth stone anvil. The split fibers were then stripped and woven into very durable thread and string. Sinew fibers could also be soaked in the mouth for a few moments to soften, then be used to bind spear and dart points to the foreshafts, knife blades to handles, feathers to mainshafts, or repair broken tools. Once dry, the sinew formed a hard, durable wrapping that could be waterproofed by applying a thin coating of melted mastic or animal skin glue.