|

Page

104

|

|

||

|

||

| Looking northeast across Marsh Valley. Putnam Mountain is in the distance, north of Inman Pass. Two peaks can be distinguished, North and South Putnam Peaks. The 600,000 year old Basalt of Portneuf Valley fills the middle of Marsh Valley. Marsh Creek is on the west side, in the foreground, and the Portneuf River is on the east side. Interstate Highway 15 runs along the middle of the lava flow. Arcuate scars in the lava flow in the center of the photo are dry waterfalls carved during the Lake Bonneville Flood about 14,500 years ago, (July, 1990). | ||

|

||

| View looking west across Marsh Valley at Old Tom Mountain (left) and Scout Mountain (right). The Basalt of Portneuf Valley fills the low part of Marsh Valley, (July, 1990). | ||

|

||

| Eastbound Oregon Short Line freight train at McCammon, (1894). Bannock County Historical Society Collection. | ||

|

||

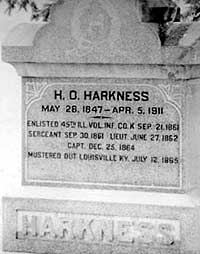

| Gravestone of H.O. Harkness, in the Gentile Cemetery, McCammon, Idaho. The memorial ironically makes no mention of the great farm, hotel, electric power generator and flour mill that Harkness constructed on the Portneuf River east of here, (June, 1989). |

Henry

O. Harkness and early McCammon

Henry

O. Harkness took over the operation of William Murphy's stagecoach service between

Corinne, Utah and the Montana gold mines in 1870 and set up operations at the

toll bridge over the Portneuf River at what is now McCammon (named for the man

who negotiated purchase of the right of way for the Oregon Short Line Railway

across the Fort Hall Indian Reservation). Harkness was an archetypal American

entrepreneur of the late 19th century and a testimony to the power of the American

Dream. In 1871, he married Murphy's widow Catherine, who had inherited her husband's

property rights to land on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation.

In 1874, Harkness turned to ranching and purchased land at Oxford, just south of the border of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. He also became partner in a bank in Corinne, Utah, which moved to Ogden in 1878. For his ranching endeavors Harkness imported the best stock and bred horses, cattle, and mules. He grew rich fields of potatoes and grain.

Henry and Catherine Harkness had no children. A year after Catherine's death in 1898, Harkness married her niece, Sarah Scott, who had come to care for Catherine during her last illness. Sarah bore five children. When he married for the second time Henry O. Harkness was 65 years old.

|

James L. Onderdonk, Territorial Controller for the Territory of Idaho, wrote, in "Idaho, Facts and Statistics" in 1885:

|

The building of the U & N Railway to Pocatello in 1878 saw the end of the freighting business and of steady use of Portneuf River toll bridge, but Harkness turned to other ways to make money. The Oregon Short Line railway bridges over the Portneuf River at McCammon were constructed near Harkness' bridge and farm. He built the grand and spacious Harkness House hotel to take advantage of the increase in traffic brought by the railroad. The chief competition was the Pacific Hotel, operated by the railroad in Pocatello, 25 miles away. By 1891, he had built a flour mill powered by waterfalls on the Portneuf. "We lead, others may follow" was advertised on bags of his flour. By 1893, the Harkness hydroelectric generating plant was established. Harkness expanded into the booming sheep business in the 1900s. In February 1905, he marketed a trainload of sheep in Chicago. In 1907, Idaho ranked third in the nation in amount of wool produced and fourth in size of flocks.

Bad floods occurred on the Portneuf River after January rains in 1911. The floodwaters destroyed some of Harkness' buildings and the stress brought on by the flood no doubt hastened his death in April 1911, at the age of 77. In June 1913, fire, a recurring scourge on the early towns of southeast Idaho, destroyed the Harkness House hotel.

Harkness' children moved away from McCammon and only remnant structures of the grand farm and ranch spread remain today.

Camp

Downey

Although

World War II was the most popular war in American history, a few people, because

of religious convictions, refused to participate in an enterprise that involved

killing one's fellow human beings. A Civilian Public Service Camp for conscientious

objectors was established on 27 acres one-half mile east of Downey using what

had been a Civilian Conservation Corps camp built in 1939 (Olinger, 1991). The

camp consisted of 21 buildings and could hold 150 persons. It was operated by

the Mennonite Central Committee, for the purpose of soil conservation and general

farm work during manpower shortages caused by the war. The camp was closed in

1946, after the fall harvest.